Japanese Pottery, Ceramics & Porcelain: History and Styles

Japan has a long and rich history in traditional arts and crafts, characterized by precision, minimalism, and deep respect for materials and their natural characteristics. Understanding this history and traditions is not complete without knowing about the time-honored tradition of famous Japanese pottery, porcelain, and ceramic craft.

Japanese pottery is not only admired internationally; traditional pottery and porcelain are very close to the hearts of Japanese people. The respect for this art in Japan is the reason behind its continuous evolution. The most important point is that it’s not just the evolved forms; the unique pottery designs of each era have been leaving their mark.

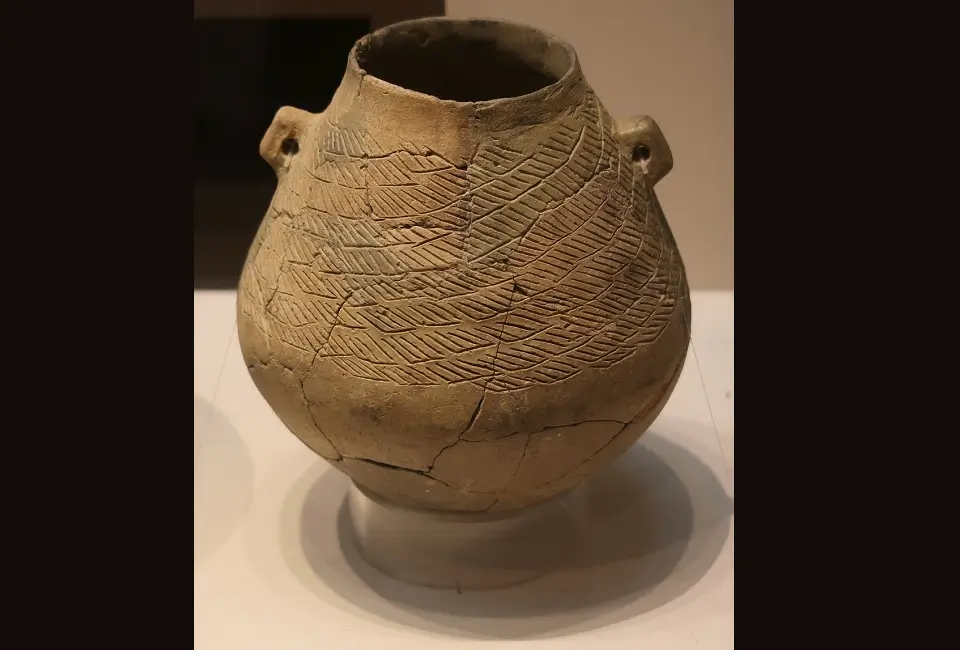

As one of the oldest arts in Japan, pottery, ceramics, and porcelain date back to the Jomon period (around 14,000 B.C. to 300 B.C.), named after the cord markings that decorated the surfaces of their clay vessels.

Let’s see how the craft of pottery and ceramics developed historically in Japan:

Pottery During Jomon Period (14,000 B.C. to 300 B.C.)

The earliest known pottery in Japan comes from this period. Japan’s first known society, the Jomon people, crafted earthenware pottery decorated with elaborate straw-rope patterns, hence the name “Jomon,” which means ” straw-rope.” This pottery was often functional and used for cooking or storage.

Straw-Rope Patterns

The term “straw-rope” pattern, or “Jomon,” which means “cord marks” or “rope pattern” in Japanese, is to describe one of the most distinctive features of pottery made during the Jomon period in Japan.

The term “Jomon” refers to the patterns created by pressing rope into the surface of wet clay. Jomon people typically made these ropes from braided or twisted plant fibers.

After shaping a pot (either by hand-building techniques such as coiling or molding), the wet surface was decorated by pressing ropes onto the clay. These ropes left a distinctive mark that created intricate patterns around the vessel.

This technique was used for aesthetic purposes and to make the pottery easier to grip.

These markings are the most characteristic feature of Jomon pottery, although they were used in conjunction with other decorative techniques, including appliqué, incision, and punctuation. The patterns were quite elaborate, often covering the entire surface of the pots.

Ceramic pottery was a key part of Jomon culture. It was used for storage, cooking, and possibly ritualistic purposes. The effort to design and decorate these utilitarian objects suggests their significant cultural importance in Japan.

The rope-patterned technique is unique to the Jomon period, and these pottery pieces provide a crucial window into understanding the culture and lifestyle of people living in the Japanese archipelago during that period.

Today, with its distinctive straw-rope patterns, Jomon pottery has a significant cultural heritage and is respected for its artistic value. Its influence is visible in modern ceramics and other art forms within and outside Japan.

Potter’s Wheel and Kiln in the Yayoi Period (300 B.C. to 300 A.D.)

Pottery in the Yayoi period saw the introduction of the potter’s wheel and kiln, techniques likely from the Korean peninsula. This period’s pottery is generally more utilitarian than decorative, often with simple cord-marked or comb-pattern decorations.

Comb-Pattern Pottery

Comb-pattern decorations, also known as “comb-marked” or “comb-impressed” patterns, are another common form of ceramic pottery decoration in Japan and various cultures worldwide.

The technique involves using a tool, often made from bone, wood, or metal, with multiple teeth like a comb. This was to create a series of parallel lines or more complex patterns on the surface of the clay before firing the clay models in the kiln.

In Japan, comb-pattern pottery is typically associated with the Yayoi period (300 BC to 300 AD), which came after the Jomon period.

While the Yayoi pottery was initially plain, the comb-pattern pottery began to appear as the period progressed. This type of pottery is called “Haji pottery,” and it’s simpler and more functional compared to the pottery of the Jomon period.

Haji pottery, including the comb-patterned variety, was typically reddish-brown when fired in oxidizing conditions. The shapes were more streamlined and less ornamental than Jomon pottery, reflecting the shift from a hunter-gatherer society to a more agrarian one.

It’s important to note that the Yayoi period also saw the introduction of the potter’s wheel to Japan, which significantly impacted the shapes and designs of the pottery produced during this time.

Thus, comb-pattern decorations mark a particular stage in the evolution of Japanese pottery, representing a blend of functional simplicity and aesthetic appeal.

Sue Ware and Haniwa in Kofun and Asuka Periods (300 A.D. to 710 A.D.)

These periods saw the rise of Sue ware or Sueki (須恵器), a type of unglazed pottery, and Haniwa (埴輪), which are terracotta clay figures for ritual use to bury them with the dead.

The introduction of Buddhism during these periods also led to the production of Buddhist figurines.

Sue ware or Sueki

Sue ware, or Sueki, is a type of unglazed, high-fired pottery produced during Japan’s Kofun (250–538) and Asuka (538–710) periods. The term “Sue” comes from the Korean word for ceramics, “Seokgi.”

Sue ware represented a significant advance in Japanese ceramics. It was among the first types of pottery in Japan to be produced using a kiln. Before this, people from the Jomon and Yayoi periods fired clay models in open pits or simple trenches to turn them into pottery.

Following are the key features and characteristics of Sue Ware

Color and Material:

Sue ware is usually gray or bluish-gray. This color is due to the firing of clay models in a reduction atmosphere, which removes oxygen during the firing process. The clay used was typically high-fired stoneware.

Shapes:

Sue ware comes in a variety of shapes, often reflecting their function. Common forms include jars, pots, and pedestals. The shapes are typically simple and elegant.

Technique:

Sue ware was typically made on a potter’s wheel, which led to more consistent shapes and thin walls. This was a contrast to the earlier hand-built Jomon and Yayoi wares.

Decoration:

Sue ware is usually unadorned, with the smooth, often lustrous surface of the fired clay as its main aesthetic feature. However, some pieces do feature incised or stamped decorations.

Function:

Sue Ware or Sueki pottery was primarily utilitarian, used for cooking, storing, and serving food. However, Japanese people also used these ceramics in traditional rituals. For example, people used specific shapes and forms of this type in burial mounds (kofun).

Sue ware was widespread throughout Japan, reflecting the growth of centralized states and the increasing influence of the mainland during the Kofun and Asuka periods.

Sue ware marked a significant technological advancement in the production of ceramics in Japan, paving the way for the development of more sophisticated pottery, ceramics, and porcelain techniques in later periods.

Today, people value these wares for their historical and archaeological significance.

Haniwa

Haniwa were terracotta clay figures used for ritual purposes and buried with the dead as funerary objects during the Kofun period, which lasted from the 3rd to 6th centuries AD in Japan.

The word ‘Haniwa’ literally means “circle of clay,” referring to its original simple cylindrical form.

Following are the key details about Haniwa:

Shapes and Forms of Haniwa:

Haniwa terracotta clay figures came in various shapes and forms, including animals, houses, tools, weapons, and human figures.

People used Haniwa human figures with kofun, the large burial mounds built for ruling class members during the Kofun period. These mounds vary in size. We can find them throughout Japan, but they are more concentrated in the Kanto region.

The human figures were often in ceremonial attire, sometimes depicted as warriors, dancers, or shamans. Their dress suggested a role in the afterlife or perhaps indicated the status or profession of the deceased.

Materials and Construction:

Haniwa were made of local red clay, which was shaped and fired at relatively low temperatures. Although the earliest Haniwa were simple in form, they became more complex and detailed over time.

Usage of Haniwa Models:

The exact purpose of Haniwa is unclear, but during the Kofun period, people used these figures in funerary rituals. They might have served to mark the boundaries of a burial site, to commemorate the deceased, or as offerings. Their forms might also have been symbolic, representing items or beings that would accompany or protect the deceased in the afterlife.

Significance:

Haniwa provides valuable insights into the culture and social structure of the Kofun period. The details of their design can tell us about the clothing, tools, and architecture of the time.

Moreover, the designs also indicate the religious or spiritual beliefs related to death and the afterlife.

Today, Haniwa is an important part of Japan’s cultural heritage. You can find Haniwa figures on display in museums. Sometimes, Japanese people also use their replicas in cultural festivals or as decorative items.

Sancai Ceramic and Asian and Buddhist Influence during the Nara Period (710 A.D. to 794 A.D.)

In the Nara period, Japan’s capital moved to Nara. This shift saw the establishment of a centralized government following the Chinese model.

Buddhism also became a state religion during this period. In terms of ceramics, the Nara period didn’t see as much development in pottery and ceramics as in other cultural achievements.

Some of the highlights of the Nara period influencing the ceramic craft of that time are as follows:

Influence from the Asian mainland:

The Nara period saw continued influence from Korea and China. However, pottery in this period was largely functional and utilitarian, made to meet society’s daily needs.

No notable distinct styles of pottery or ceramics emerged during this period.

Buddhist Influence:

The expansion of Buddhism greatly influenced the art and architecture of this period. It’s likely that ceramics also had Buddhist art and motifs influence, although few extant pieces remain for study.

During the Nara period, people used ceramics in daily life and religious settings as containers for food and other offerings.

Three-colored (Sancai) ceramics

One of the few Nara-period’s famous ceramic types is “sancai” ceramics. These ceramics were imitations of Chinese Tang dynasty ceramics.

The term “Sancai” translates to “three colors.” Sancai is a type of pottery first produced in China during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE).

The main characteristic of Sancai pottery is its colorful lead glaze, typically in three colors. These colors were mainly green, yellow, and white or cream, although we can also find these ceramics with blue and brown colors.

During the Nara period in Japan, the influence of Chinese culture was quite significant.

This influence was due to the active exchanges with the Tang Dynasty in China, which was experiencing a cultural flourishing. Sancai-style pottery found many cultural elements that came to Japan from China during this period.

Although Sancai pottery originally comes from China, Japanese potters in the Nara period created their own versions of these wares. Some key details of Sancai pottery are as follows:

Design and Technique:

Like the Chinese technique, Japanese Sancai ceramic ware was made with a white clay body and covered with a clear lead glaze.

Decorative designs were then added with colored glazes, typically in green and brown, to create the characteristic “three-color” effect.

Forms:

The forms of Sancai ware produced in Japan during the Nara period were similar to those in China. They included plates, bowls, vases, and sometimes figurines. The decorations often included floral designs and sometimes animals or humans.

Usage:

Sancai ware was used for practical purposes, such as serving food, and ceremonial or decorative purposes.

It’s worth noting that the ornate and colorful nature of Sancai ware stood in contrast to the more subdued, monochromatic pottery typical of Japanese aesthetics before and after the Nara period.

Despite the production of Sancai ceramic ware, there are only a few extant examples of Nara-period Sancai pottery.

Influence of Chinese Ceramics in the Heian Period (794 A.D. to 1185 A.D.)

The Heian period in Japan marked a significant phase in cultural development, particularly influenced by Chinese and Korean cultures. This influence was apparent in ceramics, where new techniques and styles emerged. Some key features of the ceramics of the Heian period are as follows:

Glazed Ceramics:

During the Heian period, glazed ceramics, such as green-glazed ash pottery in eastern Japan, became widespread.

While the specific techniques and color schemes used varied, the influence of Chinese and Korean pottery was evident. Predominantly, the pottery of this period featured a simple green or ash glaze. These simple hues were different from the multi-colored Sancai style of the Tang Dynasty.

Ceramic Forms and Styles:

The Heian period ceramics were largely utilitarian. Heian period Japanese people crafted these ceramics for practical uses like storage, serving food, and roof tiling.

The Heian period also witnessed the creation of religious and ceremonial items due to the growth of Buddhism. Designs were generally simple, and the beauty of the ceramics lay in their functionality and the subtle effects of the glaze.

Seto Ware:

One of the important centers for pottery during this period was the Seto region. Seto ware of the Heian period consisted largely of green-glazed stoneware. These were similar to the Yue ware produced in China during the Tang Dynasty.

Ceramic Roof Tiles:

Another significant development during the Heian period was the extensive use of ceramic roof tiles. This architectural trend, borrowed from Chinese practices, required high precision and standardization in ceramic production.

Buddhism’s Influence on Ceramics:

Buddhism’s continued spread and acceptance in Japan during this period influenced ceramics production. This is evident in the production of Buddhist ritual items, such as reliquaries.

Example of Seto Ware

It’s important to note that the Heian period set the stage for the future development of ceramics in Japan.

While the realization of certain styles and techniques did not occur until later periods, their foundation was during the Heian era.

The simplicity and focus on functionality that characterized Heian ceramics remained a significant aspect of Japanese pottery and ceramic art in the following periods.

Glazed Ceramics in the Kamakura Period (1185 A.D. to 1333 A.D.) and Muromachi Period (1336 A.D. to 1573 A.D.)

The Kamakura period marked a significant transition in Japanese history.

There was a major shift from the courtly Heian period to a time of military rule by the samurai class. This change significantly impacted all aspects of Japanese culture, including Japanese pottery and ceramics.

Some of the highlights of the Kamakura period are as follows:

Influence of Zen Buddhism:

The Kamakura period saw the introduction and spread of Zen Buddhism in Japan. The spread of Zen Buddhism significantly influenced ceramics and other arts.

The simplicity and rusticity espoused by Zen ideals influenced pottery, leading to a shift away from the more ornate and decorative styles of earlier periods.

Development of Jōmon Ware:

Jōmon ware takes its name from the prehistoric Jōmon period. However, the Kamakura period saw further development and refinement of this pottery style.

Jōmon ware is famous for its high-fired, unglazed stoneware bodies, typically reddish or brownish, and its simple, sometimes roughly finished forms.

Continuation of Seto Ware:

The production of Seto ware, which began in the Heian period, continued into the Kamakura period. The green-glazed ceramics from Seto were popular for their utility and affordability. The kilns in Seto continued to innovate, developing new glaze colors and techniques.

Mino Ware:

The Kamakura period also saw the emergence of Mino Ware.

These Mino ceramic wares would later become one of the most important types of ceramic crafts in the Momoyama and Edo periods. Mino ware of the Kamakura period was still relatively simple. Moreover, it laid the groundwork for the later developments of Shino and Oribe ware.

Tea Ceremonies and Japanese Ceramics in the Kamakura Era:

The early foundations of the tea ceremony (chadō or sado), which would later profoundly impact Japanese ceramics, began to develop during the Kamakura period.

The aesthetics of the tea ceremony, which emphasized simplicity, rusticity, and the beauty of imperfection, aligned with Zen Buddhism’s ideals and significantly influenced the development of Japanese ceramics during the Kamakura period.

Mino Ware

Mino ware (美濃焼, Mino-yaki) refers to Japanese pottery produced in the Mino area, located in present-day Gifu Prefecture.

The Mino wares have a long history dating back to the Kamakura period. However, they became particularly prominent during the Momoyama period (1573–1603) and early Edo period (1603–1868).

The two most famous types of Mino ceramic ware are Oribe ware and Shino ware.

These types got their names from the influential tea masters Furuta Oribe and Shino Soshin of the late 16th century. Mino ware’s connection to the tea ceremony has been central to its development, with many of its most celebrated forms being tea utensils.

Commonness between the Ceramic and Pottery Craft of the Kamakura and Muromachi Periods

While pottery production continued throughout the Muromachi period, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish specific styles unique to this era.

The pottery and ceramic production of these periods continued techniques from previous periods. However, the influence of Zen Buddhism and the evolving culture around the tea ceremony led to some shifts in aesthetics and form.

The Muromachi period is often associated with the rise of the wabi-sabi aesthetic.

The wabi-sabi concept is about finding beauty in imperfection and transience. The unpredictable firing results make each Shino ware piece unique.

The philosophy of wabi-sabi significantly influenced the development of tea ceremony utensils, including ceramics.

The aesthetics of the tea ceremony began to favor more rustic and natural-looking pottery. This was often with irregular shapes and textures that would later become characteristic of certain styles of Mino ware, including Shino and Oribe, in the following Azuchi-Momoyama period.

Moreover, this period also witnessed increased interaction with the Korean Peninsula and China.

The imports of Chinese and Korean ceramics substantially impacted Japanese pottery styles and techniques. During this time, many Korean potters were brought to Japan due to the invasions by Toyotomi Hideyoshi. This influence of Korean pottery later resulted in many new styles in the Momoyama and Edo periods.

Therefore, we cannot pin specific pottery styles to the Muromachi period. However, that time’s aesthetics, tastes, and foreign influences contributed to significant developments in Japanese ceramics.

Azuchi Momoyama Period (1573 A.D. to 1603 A.D.)

This period saw the creation of distinctly Japanese styles such as Oribe, Shino, and Raku wares, including Yellow Seto and Black Seto wares. All of these were deeply connected with the aesthetics of the Japanese tea ceremonies.

These wares are often asymmetric, featuring abstract, painted designs in iron, copper, and cobalt (Oribe and Shino) or subtle, earthy glazes and the mark of the artist’s hand (Raku).

These styles marked a shift toward rusticity and the celebration of natural, organic qualities, a change from earlier periods’ more refined, formal ceramic wares.

Oribe Ware

The name Oribe ware comes from the 16th-century tea master Furuta Oribe. Oribe ware is one of the many types of Mino ware ceramics from Japan’s Mino and Seto areas of Gifu Prefecture.

It emerged in the late 16th to early 17th century during the Azuchi-Momoyama period. The Oribe ceramic ware is famous for its copper-green glaze and bold, unconventional designs.

Following are more details about Oribe Ware:

Design:

Oribe ceramics are quite distinct and instantly recognizable. They are famous for their fluid, somewhat whimsical shapes and the use of bold and contrasting colors. Some common motifs include natural elements such as birds, plants, and geometric patterns.

Glazes:

One of the most distinctive features of Oribe ware is its green glaze.

This green glaze of Oribe ware comes from copper.

The green color is due to the “reduction firing” of the clay model of Oribe ware, where oxygen is removed from the kiln during the firing process.

In addition to green, Oribe ware features white and black glazes; Japanese pottery and ceramic craftsmen often combine glazes of different colors.

Shapes:

Oribe ware comes in a variety of shapes. However, their origin was for the use of tea ceremonies. This includes not only tea bowls but also various types of dishes, vases, and other utensils.

Oribe vs. other Mino wares

Oribe ware stands out from other Mino wares due to its bold painted decoration, the use of the copper-green glaze, and the characteristic irregular shapes.

For comparison, Shino ware, another type of Mino ware, is generally known for its thick, white, feldspar glaze and subtle painted decorations.

Oribe ware reflects the aesthetics of wabi-sabi, appreciating beauty in imperfection and naturalness. These characteristics are at the core of the tea ceremony.

Its creation also marks a significant period in Japanese ceramics. The significant change was that the artisans began to be recognized as individual artists rather than anonymous craftsmen.

Raku Ware

Raku ware is deeply connected with the Japanese tea ceremony and is characterized by its simplicity and subtlety. It represents a significant shift from the traditional method of creating pottery on a wheel to a much more hands-on technique.

Here are some key aspects of Raku ceramic ware:

Technique

Raku ware is typically hand-shaped instead of being shaped by a potter’s wheel.

Hand shaping gives each piece a distinctly individual character, reflecting the hand of its maker. The pieces are typically quite thick and somewhat irregular, embodying the aesthetic of wabi-sabi, or beauty in imperfection.

Firing and Glazing

The firing process for Raku ware is also unique. Pieces are taken from the kiln at their maximum temperature (about 1000°C, lower than most other pottery).

After that, they are cooled quickly, sometimes in the open air or in a container filled with combustible material. This process, known as post-firing reduction, can create striking and unpredictable patterns and colors on the pottery’s surface.

The glazes used in Raku ware, particularly the distinctive crackled glaze often seen in Raku pieces, also contribute to these unique effects.

Forms

Many Raku pieces are used for tea ceremonies, and typical forms include tea bowls (chawan), water containers, and other tea utensils.

Philosophy

The philosophy behind Raku ware is tied to Zen Buddhism, which influenced the tea ceremony’s development. The emphasis is on simplicity and naturalness, reflected in the modest forms and earthy appeal of Raku ware.

Raku Family

The Raku family, now in its 15th generation (as of 2021), continues the tradition of Raku ware in Kyoto. Each head of the family takes the name “Raku,” often posthumously.

This unique combination of technique, form, and philosophy makes Raku ware a significant part of Japanese ceramic art. It’s appreciated worldwide, and potters have adapted the Raku firing technique globally.

Shino Ware

Shino ware is a Japanese pottery most identifiable by its thick white glazes, texture, pinholes, or “sauna.” It was first fired during the Momoyama period in kilns in the Mino and Seto areas. Shino ceramic ware, along with Oribe, is a type of Mino ware.

Here are some key features and characteristics of Shino ware:

Glaze:

Shino ware is best known for its thick, white glaze, which is composed of ground feldspar and has a somewhat rough texture. Small pinholes or pits often form in the glaze during the firing process, giving it a distinct appearance.

Decoration:

The white glaze of Shino ceramic ware acts as a canvas for subtle decorations painted in iron oxide. The inspiration behind these designs is often from nature and can include motifs such as birds, grasses, and flowers.

Shapes and Forms:

Shino ware is often associated with tea utensils, especially tea bowls (chawan). The shapes are generally simple and unpretentious, following the wabi-sabi aesthetics of the tea ceremony.

Firing Process:

Shino ware is fired in wood-burning kilns. This process can take a significant amount of time and affects the final appearance of the pottery. The ash from the wood can settle on the pieces during firing and interact with the glaze to create various effects.

Variations:

There are several variations of Shino, such as Muji-Shino (plain Shino), E-Shino (painted Shino), and Nezumi-Shino (gray Shino).

Shino ware is famous for its rustic beauty and subtle elegance, embodying the tea philosophy’s wabi-sabi concept.

Yellow Seto (Ki-Seto) and Black Seto (Setoguro)

Yellow Seto (Ki-Seto): Yellow Seto is one of the major types of Mino ware. As its name suggests, Yellow Seto is recognized for its warm yellow glaze.

The glaze is typically rich in iron, which gives it its distinctive color. It was introduced during the late Kamakura period (1185-1333) but flourished during the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1603). Yellow Seto wares often have simple and rustic forms, echoing the influence of the wabi-sabi aesthetic.

Black Seto (Setoguro): Black Seto ware is notable for its glossy black glaze, achieved through a specific reduction firing process.

The clay models are fired and removed from the kiln while still hot, a process known as “cooling in reduction.” The sudden temperature change causes the glaze to turn a lustrous black, often with subtle variations and effects.

Moreover, just like Yellow Seto, Black Seto ware is particularly associated with the tea ceremony and is prized for its understated, elegant beauty.

Both Yellow Seto and Black Seto ceramic wares reflect the tradition of Mino ware in their high quality and aesthetic principles. These aesthetic principles align closely with the ideals of the Japanese tea ceremony. Their distinct color palettes and the techniques used to achieve them also represent the innovation and diversity of Japanese ceramics.

Edo Period (1603 A.D. to 1868 A.D.)

The Edo period marked the establishment and flourishing of many kilns across Japan. It’s also famous for the rise of the sophisticated styles of Kutani, Satsuma, and Arita porcelain, often richly decorated with overglazed enamels and gold.

Kutani Porcelain (Kutani-yaki)

Kutani porcelain originated in the Kaga province (now Ishikawa Prefecture) in the mid-17th century. The word “Kutani” means “Nine Valleys,” which was the name of the area where the first kiln was established.

Some of the notable points about Kutani porcelain are as follows:

Design of Kutani porcelain objects:

Kutani porcelain is famous for its intricate designs. These designs are characterized by bold and lavish coloring – typically in red, green, yellow, purple, and deep blue shades. The designs often depict people, landscapes, birds, and other elements of nature.

Types of Kutani porcelain:

Kutani porcelain can be divided into two main types. These are “Ko-Kutani” (Old Kutani), produced in the 17th century, and “Saiko Kutani.” These names refer to the revival of the Kutani ware, which started in the 19th century.

Popularity of Kutani porcelain:

Kutani porcelain enjoyed a resurgence in the 19th century during the Meiji era and remains highly sought after by collectors today.

Satsuma Porcelain (Satsuma-yaki)

Satsuma ware originated in the late 16th century in the Satsuma domain, which is now Kagoshima Prefecture, located in the southern part of Kyushu Island.

- Design: Satsuma ware is known for its cream-colored, crackled glaze with elaborate polychrome and gold decorations. These designs often feature detailed scenes of people, animals, nature, and immortality themes.

- Popularity: Satsuma ware became very popular in the West after its display at the Paris Exposition in 1867. Much of the Satsuma seen in the West is actually “export ware.” The design of these pieces was specifically for export in the late 19th—early 20th centuries.

Arita Porcelain (Arita-yaki)

Also known as Imari ware, Arita porcelain is a broad term for porcelain from the Arita area of Saga Prefecture, Kyushu. Production began in the early 17th century.

Some of the key features of Imari ware are as follows:

Design:

Arita ware is characterized by its fine white porcelain body, painted cobalt blue under the glaze. Over time, it also incorporated overglazed enamel decorations, often red, green, and gold, with complex designs of nature, animals, and people.

Types:

Early Arita ware (also known as Early Imari or Shoki-Imari) is generally used underglaze blue. From the mid-17th century, Kakiemon-style Arita (featuring a bright palette on a milky-white body) and Kinrande-style Arita (characterized by lavish gold decoration) became popular. The West also uses the term “Imari” to refer to Arita ware exported from the port of Imari in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Popularity:

Arita ware was extensively exported to Europe through the Dutch East India Company, significantly impacting European porcelain styles.

These styles of Japanese porcelain are celebrated for their artistry and craftsmanship. They continue to be produced today, keeping alive centuries-old traditions and techniques.

Modern Era Japanese Pottery, Ceramics & Porcelain

Japan continues to produce traditional styles and contemporary ceramics. Renowned ceramic potters such as Shoji Hamada and Kanjiro Kawai have significantly contributed to modern pottery, combining traditional techniques with their artistic philosophies.

Each region in Japan tends to have its distinctive pottery style, often named after the region itself.

For example, Bizen ware from Okayama Prefecture is known for its high-temperature firing without glaze, which results in unique earthy colors. Similarly, Seto ware from Aichi Prefecture is famous for its high-quality pottery, ceramics, and porcelain. These regional variations add to the rich tradition of Japanese pottery, porcelain, and ceramic art.

A long-term ex-pat in Japan, Himanshu comes with an IT background in SAP consulting, IT Business Development, and then running the country operations of an IT consulting multinational. Himanshu is the co-founder and Managing Director of ReachExt K.K. and EJable.com. He is also an Advisory Board Member of a Silicon Valley AI/IoT startup.